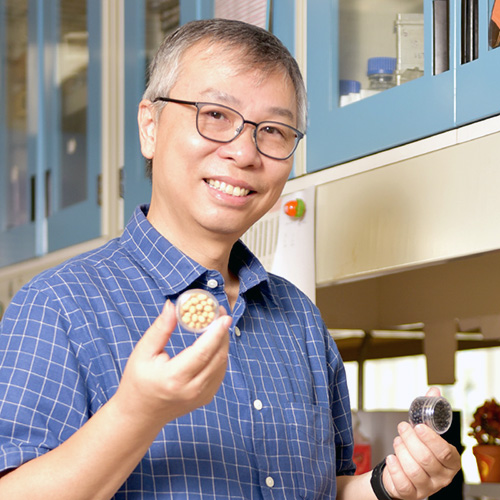

Professor LAM Hon Ming

(School of Life Sciences)

Our Eminent Scientists @ CUHK:

Perseverance in Bringing Soybean Home and Reaching Out to the World

“Ren Shu”, the ancient name for soybean, appeared quite a few times in the “Classics of Poetry” (Shijing), China’s oldest existing collection of poetry. This suggests that soybean was already a quintessential agricultural crop in China in as early as the Western Zhou dynasty (the 11th to 7th centuries BC). Once a major exporter of the crop, China, in recent decades, has become the world’s largest importer. Choh-Ming Li Professor of Life Sciences, Professor LAM Hon-Ming, devoted decades of scientific research to realize his dream of “bringing soybean home”. Combining cutting edge technological know-how with traditional wisdom in breeding, Professor Lam has developed strains of stress-tolerant soybean that can grow on marginal lands that are dry and nutrient-deprived, allowing the impoverished farmers to increase the yield and therefore income. Capitalizing on the nitrogen fixation capacity unique to legume crops, the marginal lands can be enriched at the same time. More importantly, the need for fertilizers which are detrimental to the environment in its use and production can be reduced, thus contributing to the development of sustainable agriculture. Throughout the years, Professor Lam has generously shared his soybean research experience and insight by training students and researchers from other countries. One day, our Hong Kong-developed soybean strains may just take root in various parts of the world.

The Prologue of Soybean Homecoming

In his pursuit of a career as a scientist, Professor Lam hopes to find ways to solve some of the world’s problems through science and contribute to improving people’s livelihood. By the end of his Ph.D. training, he made a crucial career choice. While many of his cohorts chose to specialize in medical research, he felt that the world’s food security issue was not given enough attention. Every minute, 17 people die of hunger globally, according to the United Nations statistics. The culprits behind are many, but the indisputable fact is, as the world’s population grow incessantly, arable lands are disappearing, leaving us with less land to feed more people. It is thus critical that the crop productivity be improved. As a result, Professor Lam opted to go into the field of plant molecular biology for his post-doctoral training, delving into the mechanisms of nitrogen metabolism in plants. He immersed himself in learning cutting edge science and technology to prepare for his future career in applied agricultural research.

Upon his return to Hong Kong, joining CUHK in 1997, Professor Lam visited many pioneers in crop study in China. He wished to find out the state of research, the problems and bottlenecks so he could better position himself. At that time, rice, the primary staple food for Asian cultures, was the mainstream choice in crop research. Soybean, on the other hand, was not in the limelight. Professor Lam felt that many have failed to recognize one of soybean’s special qualities – its nitrogen fixation capability.

Plants need nutrients in soil to grow. Fertilizers, main components being nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, are usually added to boost the growth and yield. However, the chemicals can pollute the water source. The emission of greenhouse gases in the production of fertilizers is another problem. Root nodules in legume plants work wonders – they can “fix” the nitrogen abundant in air into the soil. This capability enriches the nutrient-deprived lands, requiring less use of fertilizers. Therefore, growing soybeans can help “repair” the marginal lands, at the same time, reducing cost to the farmers and the environment. Additionally, soybean is rich in quality protein that is cheap and easily absorbable by the human body. Soy foods provide a good alternative to meat in the human diet. Soy milk is often referred to as milk for the poor. It is definitely worth promoting. Professor Lam decided then that he was going to build his career in soybean research.

China houses 20% of the world’s population. But she has only 9% of the world’s arable lands. The problem of food security was imminent in China. Inspired by Professor SHAO Guihua, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, who devoted decades in the field study of salt tolerance in soybean, Professor Lam believes that stress-tolerant strains of soybean that can grow in marginal lands can also help reclaim some otherwise waste lands, thereby increasing arable lands. Hardship of farmers on these bad lands can be eased. These were ample reasons to support his career choice. Traditional breeding methods are laborious and time-consuming. Professor Lam introduced the state-of-the-art molecular biotechnology he learned in his post-doctoral training to complement the wisdom in traditional breeding in his search for a breakthrough.

Professor Guihua SHAO passed on her field knowledge to Professor LAM and his team without reservation. (Photo credit: CUHK CPRO)

In 2007, the world witnessed a technological revolution in “Whole Genome Sequencing” (WGS). The conventional single gene sequencing, in comparison, was lagging way way behind in efficacy. Although well trained in molecular biotechnology, in the face of the emerging new technology, even Professor Lam had to learn from scratch. He advises that technological advancement will offer new tools to the scientists. Staying in one’s own comfort zone, one will easily miss the chance for a leap forward.

The Concerted Journey of Soybean Homecoming

Professor Lam realized the potential of WGS in fast-forwarding his soybean research. However, Hong Kong did not yet have the necessary equipment. He approached BGI-Shenzhen with a collaborative proposal. Joining force with its bioinformatics team, Professor Lam decoded the genomes of 31 wild and cultivated soybeans and showcased the much higher degree of genetic diversity in wild soybean. The ground breaking findings were published in Nature Genetics in 2010 and chosen for highlight as a cover story. The paper laid the foundation for future soybean and crop research. Professor Lam encourages young researchers to be humble and foster collaborative research with partners sharing the same vision. Learn from and complement each other, there will not be insurmountable obstacles.

Decoding soybean genomes was only the first step; identifying the salt-tolerant gene, dream of Professor Shao’s, was next. Limited by the technological know-how, Professor Shao was unable to complete the arduous task before her retirement. Professor Lam promised to carry her torch and continue the work. He spearheaded the combination of genetics and molecular biology with bioinformatics approaches and successfully identified and cloned a new salt-tolerant gene from wild soybean. The findings were published in Nature Communications in 2014. This has since become the benchmark approach and inspire many national and international soybean researchers, the younger generation in particular.

CUHK School of Life Sciences Greenhouse – The “origin” of Soybean Homecoming

Publication of high quality, high impact, high flying papers is important and enticing, but to Professor Lam, putting his research to use on the land, making a leap from laboratory to farmland, is more compelling. Known for aridity and poor farmland quality, Northwest China is plagued by concentration of marginal lands and waste lands. Professor Lam found partnership in Professor ZHANG Guohong of the Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Using non-transgenic approach, they developed strains of soybean that are salt-tolerant and drought-tolerant at the same time and field tested them in Gansu, truly “bringing soybean home”. Among the strains developed, “Longhuang No. 1, 2, and 3” have been approved for use in Gansu province. Since 2016, the cumulative acreages of these varieties in semi-arid and drought-stricken areas in the Loess Plateau have exceeded 610,000mu, or about 40,000 hectares, about the total area of more than five Hong Kong Islands. In 2022, “Longhuang No. 2, and 3” are selected by Gansu province as two of the recommended soybean cultivars to use in soybean-maize strip-intercropping practices. It is now pilot-tested in fields spanning 200,000mu.

Reaching out to the World

In 2017, Professor Lam and his team held the Worldwide Universities Network (WUN) scientific conference in CUHK. Leading scholars and young scholars in legume research gathered and engaged in avid exchange of ideas. Many collaborative projects have emerged from this occasion, including the joint effort in constructing the first reference grade wild soybean genome. In recent years, Professor Lam has taken part in deciphering many more soybean genome resources with scientists in China mainland, Korea and the US. All these initiatives are pivotal as they provide essential tools for scientists worldwide to improve cultivated soybean varieties in the future.

Professor Lam aims to take his research to where it is needed, Africa being one of the possible targets. Drought has been persistent in the African continent and is expected to continue. Only a handful of rich farmers may mitigate the problem by investing massively on an irrigation system, drawing on already scanty water resources. Most small farmers can only submit themselves to the will of nature. Drawing on the experience in Northwest China, Professor Lam and his South African counterparts are joining hands in the development of drought-tolerant strains that can also resist the pests indigenous to South African soil, improve the soil quality, increase yields thus income for farmers. In spite of the COVID-19 pandemic, field tests have already started in South Africa. Other than South Africa, Professor Lam has also engaged in exploratory collaboration with countries like Pakistan. It is his hope that, through scientific exploration, people from different parts of the world can come together in solving the world’s problems.

Professor Hon-Ming LAM (second from right), Professor Ting-Fung CHAN (first from left) and Professor Ndiko LUDIDI (first from right), their collaborator in South Africa, are currently working on new stress-tolerant soybean cultivars. (Photo credit: RGC-AoE Center for Genomic Studies on Plant-Environment Interaction for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Security)

Text: Angela HUNG | Editing: Christine LING